A Candle For Remembering

May this memorial candle lights up the historical past of our beloved Country: Rwanda, We love U so much. If Tears could build a stairway. And memories were a lane. I would walk right up to heaven. To bring you home again. No farewell words were spoken. No time to say goodbye. You were gone before I knew it And. Only Paul Kagame knows why. My heart still aches with sadness. And secret tears still flow. What It meant to lose you. No one will ever know.

Rwanda: Cartographie des crimes

Rwanda: cartographie des crimes du livre "In Praise of Blood, the crimes of the RPF" de Judi Rever

Kagame devra être livré aux Rwandais pour répondre à ses crimes: la meilleure option de réconciliation nationale entre les Hutus et les Tutsis.

Let us remember Our People

You can't stop thinking

Don't you know

Rwandans are talkin' 'bout a revolution

It sounds like a whisper

The majority Hutus and interior Tutsi are gonna rise up

And get their share

SurViVors are gonna rise up

And take what's theirs.

We're the survivors, yes: the Hutu survivors!

Yes, we're the survivors, like Daniel out of the lions' den

(Hutu survivors) Survivors, survivors!

Get up, stand up, stand up for your rights

et up, stand up, don't give up the fight

“I’m never gonna hold you like I did / Or say I love you to the kids / You’re never gonna see it in my eyes / It’s not gonna hurt me when you cry / I’m not gonna miss you.”

The situation is undeniably hurtful but we can'stop thinking we’re heartbroken over the loss of our beloved ones.

"You can't separate peace from freedom because no one can be at peace unless he has his freedom".

Malcolm X

Welcome to Home Truths

The year is 1994, the Fruitful year and the Start of a long epoch of the Rwandan RPF bloody dictatorship. Rwanda and DRC have become a unique arena and fertile ground for wars and lies. Tutsi RPF members deny Rights and Justice to the Hutu majority, to Interior Tutsis, to Congolese people, publicly claim the status of victim as the only SurViVors while millions of Hutu, interior Tutsi and Congolese people were butchered. Please make RPF criminals a Day One priority. Allow voices of the REAL victims to be heard.

Everybody Hurts

“Everybody Hurts” is one of the rare songs on this list that actually offers catharsis. It’s beautifully simple: you’re sad, but you’re not alone because “everybody hurts, everybody cries.” You’re human, in other words, and we all have our moments. So take R.E.M.’s advice, “take comfort in your friends,” blast this song, have yourself a good cry, and then move on. You’ll feel better, I promise.—Bonnie Stiernberg

KAGAME - GENOCIDAIRE

Paul Kagame admits ordering...

Paul Kagame admits ordering the 1994 assassination of President Juvenal Habyarimana of Rwanda.

Why did Kagame this to me?

Can't forget. He murdered my mother. What should be my reaction? FYI: the number of orphans in Rwanda has skyrocketed since the 1990's Kagame's invasion. Much higher numbers of orphans had and have no other option but joining FDLR fighters who are identified as children that have Lost their Parents in Kagame's Wars inside and outside of Rwanda.If someone killed your child/spouse/parent(s) would you seek justice or revenge? Deep insight: What would you do to the person who snuffed the life of someone I love beyond reason? Forgiving would bring me no solace. If you take what really matters to me, I will show you what really matters. NITUTIRWANAHO TUZASHIRA. IGIHE KIRAGEZE.If democracy is to sell one's motherland(Africa), for some zionits support, then I prefer the person who is ready to give all his live for his motherland. Viva President Putin!!!

RPF committed the unspeakable

The perverted RPF committed the UNSPEAKABLE.Two orphans, both against the Nazi world. Point is the fact that their parents' murder Kagame & his RPF held no shock in the Western world. Up to now, the Rwandan Hitler Kagame and his death squads still enjoy impunity inside and outside of Rwanda. What goes through someone's mind as they know RPF murdered their parents? A delayed punishment is actually an encouragement to crime, In Praise of the ongoing Bloodshed in Rwanda. “I always think I am a pro-peace person but if someone harmed someone near and dear to me, I don't think I could be so peaceful. I would like to believe that to seek justice could save millions of people living the African Great Lakes Region - I would devote myself to bringing the 'perp' along to a non-happy ending but would that be enough? You'd have to be in the situation I suppose before you could actually know how you would feel or what you would do”. Jean-Christophe Nizeyimana, Libre Penseur

Inzira ndende

Search

Hutu Children & their Mums

Look at them ! How they are scared to death. Many Rwandan Hutu and Tutsi, Foreign human rights advocates, jounalists and and lawyers are now on Death Row Waiting to be murdered by Kagame and his RPF death squads. Be the last to know.

Rwanda-rebranding

Rwanda-rebranding-Targeting dissidents inside and abroad, despite war crimes and repression

Rwanda has “A well primed PR machine”, and that this has been key in “persuading the key members of the international community that it has an exemplary constitution emphasizing democracy, power-sharing, and human rights which it fully respects”. It concluded: “The truth is, however, the opposite. What you see is not what you get: A FAÇADE”

Rwanda has hired several PR firms to work on deflecting criticism, and rebranding the country.

Targeting dissidents abroad

One of the more worrying aspects of Racepoint’s objectives

was to “Educate and correct the ill informed and factually

incorrect information perpetuated by certain groups of expatriates

and NGOs,” including, presumably, the critiques

of the crackdown on dissent among political opponents

overseas.

This should be seen in the context of accusations

that Rwanda has plotted to kill dissidents abroad. A

recent investigation by the Globe and Mail claims, “Rwandan

exiles in both South Africa and Belgium – speaking in clandestine meetings in secure locations because of their fears of attack – gave detailed accounts of being recruited to assassinate critics of President Kagame….

Ways To Get Rid of Kagame

How to proceed for revolution in Rwanda:

- The people should overthrow the Rwandan dictator (often put in place by foreign agencies) and throw him, along with his henchmen and family, out of the country – e.g., the Shah of Iran, Marcos of Philippines.Compaore of Burkina Faso

- Rwandans organize a violent revolution and have the dictator killed – e.g., Ceaucescu in Romania.

- Foreign powers (till then maintaining the dictator) force the dictator to exile without armed intervention – e.g. Mátyás Rákosi of Hungary was exiled by the Soviets to Kirgizia in 1970 to “seek medical attention”.

- Foreign powers march in and remove the dictator (whom they either instated or helped earlier) – e.g. Saddam Hussein of Iraq or Manuel Noriega of Panama.

- The dictator kills himself in an act of desperation – e.g., Hitler in 1945.

- The dictator is assassinated by people near him – e.g., Julius Caesar of Rome in 44 AD was stabbed by 60-70 people (only one wound was fatal though).

- Organise strikes and unrest to paralyze the country and convince even the army not to support the dictaor – e.g., Jorge Ubico y Castañeda was ousted in Guatemala in 1944 and Guatemala became democratic, Recedntly in Burkina Faso with the dictator Blaise Compaoré.

Almighty God :Justice for US

Hutu children's daily bread: Intimidation, Slavery, Sex abuses led by RPF criminals and Kagame, DMI: Every single day, there are more assassinations, imprisonment, brainwashing & disappearances. Do they have any chance to end this awful life?

Killing Hutus on daily basis

RPF targeted killings, very often in public areas. Killing Hutus on daily basis by Kagame's murderers and the RPF infamous death squads known as the "UNKNOWN WRONGDOERS"

RPF Trade Mark: Akandoya

Rape, torture and assassination and unslaving of hutu women. Genderside: Rape has always been used by kagame's RPF as a Weapon of War, the killings of Hutu women with the help of Local Defense Forces, DMI and the RPF military

The Torture in Rwanda flourishes

Fighting For Our Freedom?

We need Freedom, Liberation of our fatherland, Human rights respect, Mutual respect between the Hutu majority and the Tutsi minority

KAGAME VS JUSTICE

Tuesday, March 12, 2019

By Guillaume Kress, Global Research

[Since 1994, the world witnesses the horrifying Tutsi minority (14%) ethnic domination, the Tutsi minority ethnic rule with an iron hand, tyranny and corruption in Rwanda. The current government has been characterized by the total impunity of RPF criminals, the Tutsi economic monopoly, the Tutsi militaristic domination, and the brutal suppression of the rights of the majority of the Rwandan people (85% are Hutus)and mass arrests of Hutus by the RPF criminal organization =>AS International]

[Since 1994, the world witnesses the horrifying Tutsi minority (14%) ethnic domination, the Tutsi minority ethnic rule with an iron hand, tyranny and corruption in Rwanda. The current government has been characterized by the total impunity of RPF criminals, the Tutsi economic monopoly, the Tutsi militaristic domination, and the brutal suppression of the rights of the majority of the Rwandan people (85% are Hutus)and mass arrests of Hutus by the RPF criminal organization =>AS International]The well-expected then created ground on which they had adopted Kagame’s blatant official scenario

Violence broke out the following morning, on April 7. The President of the UN Security Council asked the UN Secretary General to collect information regarding the attacks and report it to the Security Council as soon as possible. No news would come until June, when René Dégni, a UN envoy in Rwanda, acknowledged that the shooting of the Dassault Falcon 50 jet had triggered the genocide and requested that a commission be created to examine the issue. Other reports would later attest to his statement and add that the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) was involved in the conspiracy. The UN mysteriously rejected Dégni’s request on the grounds that the organization did not have the necessary budget for such an undertaking.1

Months after the massacre, on November 8, the UN Security Council created the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), an international ad hoc tribunal responsible for bringing to justice the individuals charged with organizing the violence committed in Rwanda and its neighboring territories between January 1 1994 and December 31 1994. Although Habyarimana’s death clearly fell within this time period, the ICTR nevertheless went on to declare that any investigation into the event was beyond the tribunal’s mandate. Why did the ICTR make this decision in 1997 and what does it reveal today about international public law?

Upon closer examination, the ICTR carries evidence for Paul Kagame’s complicity in the Habyarimana attacks and in the replacement of a multi-ethnic and power-sharing coalition government with a disruptive and criminal military regime. The evidence undermines the UN’s legitimacy 1) by falsifying its official “Tutsi massacre” thesis, 2) by exposing the role of some Security Council members in facilitating the RPF’s rise to power, and 3) by pointing to the inapplicability of its championed common law and multiparty electoral systems in heterogeneous ethnic settings. This triple threat pushes the UN to preserve its legitimacy by forcing the ICTR not to take into account the evolution of knowledge on the genocide. Therefore, Kagame can claim diplomatic immunity and continue to exercise his hegemonic influence in the Great Lakes region without signing the 1998 Rome Statute so long as the UN remains in its current vulnerable position.

Davenport and Stam use an aggregating methodology that we find logical and plausible in dealing with a very confusing environment—working from data estimating total pre-April 6, 1994 Tutsi and Hutu members of the population, and post-July 1994 numbers of Tutsi survivors. We use a similar method in Enduring Lies, taking Rwanda census data breakdowns of Tutsi and Hutu numbers as of August 1991, and post-July 1994 estimates of Tutsi survivors ranging from 300,000 to 400,000. Without going into too many details here, we found that, for example, on the assumption of 800,000 total deaths for the period April through July, 1994, plausible estimates of Hutu and Tutsi deaths ranged from between 100,000 and 200,000 Tutsi deaths, and between 600,000 and 700,000 Hutu deaths.[26] We also show, again relying on the logic of Davenport and Stam’s method, the crucial lesson that (quoting from our book) “the greater the total number of deaths, the greater the number of Hutu deaths overall, and the greater the percentage comprised of Hutu.”[27]

Hence, the following crucial exchange between Corbin and Stam (30:31):

Allan Stam: If a million people died in Rwanda in 1994—and that’s certainly possible—there is no way that the majority of them could be Tutsi.

Jane Corbin: How do you know that?

Allan Stam: Because there weren’t enough Tutsi in the country.

Jane Corbin: The academics calculated there had been 500,000 Tutsis before the conflict in Rwanda; 300,000 survived. This led them to their final controversial conclusion.

Allan Stam: If a million Rwandans died, and 200,000 of them were Tutsi, that means 800,000 of them were Hutu.

Jane Corbin: That’s completely the opposite of what the world believes happened in the Rwandan genocide.

Allan Stam: What the world believes, and what actually happened, are quite different.

Notice the conditional “if” with which Stam begins his explanation. He could have stated “If 500,000 people died,” or “If 2 million people died,” and their method would have generated different results. It is also notable that the 38 dismiss Davenport and Stam simply as academics who “worked for a team of lawyers defending the génocidaires at the ICTR.” In fact, Davenport and Stam started work in Rwanda under the auspices of the U.S. Agency for International Development, and at one time Stam served in the U.S. Army Special Forces. And the defense counsels before the ICTR often were defending clients eventually found to be innocent of all charges, but here the same clients are found guilty in advance by the 38, who call all of them “génocidaires,” and would presumably deny them the right to defend themselves.

|

| President Juvenal Habyarimana |

|

| Trévic |

Back then – and still today – few outsiders understood the lived particularities of Rwanda’s ethnic democracy in the lead up to the genocide (1990-1994).2 Therefore, when Kagame assassinated President Juvenal Habyarimana on the night of April 6 and 7 and Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana the following morning, a narrative centered on a scapegoat, the Hutu extremist, captured the imagination of almost every outsider who struggled to make sense of the conflict.3

|

| Nathalie Poux |

Proponents of this narrative also describe Habyarimana’s inner circle of relatives and friends, the Akazu, as a group of violent and racist radicals, often intellectuals, with a ‘zero ethnic Tutsi’ policy. This Hutu extremist faction, a cadre of Habyarimana’s MRND party for which democratization meant a likely loss of power, was labelled extremist because it did not refrain from killing moderates. From 1991 to 1992, numerous indiscriminate attacks (with bombs and grenades, among other weapons) were attributed to this faction’s ethnic hating ‘Hutu power’ ideology. As a result, many believed that the Akazu orchestrated Habyarimana’s assassination in 1994.

Another Hutu extremist faction was the Interahamwe, a militia formed by groups of young people from the MRND party. Supporters of the official narrative tell us it carried out much of the killing in 1994 and founded the RTLM, a radio station accused of hate speech and treason for broadcasting where Tutsis were fleeing during the genocide. Their attacks aggravated ethnic tensions by adding pressures to democratize.6 Ultimately, this violent faction, like the Akazu, provided Kagame with the necessary pretext for engaging in armed conflict: namely, protecting the people from the MRND. As we will see, however, the official narrative oddly ignores the role these extremist factions had after the genocide in providing the ICTR with its incentive to prosecute Hutu extremists at all costs and overlook the RPF’s role in pillaging the African Great Lakes region.

In sum, the official narrative tells us that the period leading up to the assassination was one of exacerbating ethnic tensions caused by highly violent Hutu extremist factions, many of which the interim government could not put down.7 Kagame and the RPF resumed hostilities against Hutu extremists on the morning after Habyarimana’s assassination in order to protect the Tutsi population. They came out victorious several months later, in July, and have ruled Rwanda ever since.

Contesting the Official Narrative

For a complete historical account of the Rwandan genocide, we cannot omit the lived particularities of Rwanda’s ethnic democracy in the lead up to the genocide. It is therefore necessary to question the validity of the Hutu extremist narrative. A brief overview of the Hourigan, Bruguiere, and Trevidic reports is useful here. The reports were written at different times by judges who sought to revise the official narrative via an examination of Kagame’s role in the shooting down of the Falcon 50.

|

| Paul Kagame |

The UN Security Council denied the existence of the Hourigan Report until a Canadian source published it in March 2000. That year, the families of the crew members who perished on the Falcon 50 had urged a French judge called Jean-Louis Bruguiere to investigate the causes of the assassination.10 Upon his request, in May 2000, the UN Security Council sent Bruguiere a copy of the Hourigan Report (albeit reluctantly), which allowed him to add to Hourigan’s conclusions by examining the origins of the missiles used in the assassination and by recording more self-incriminating testimonies of high-ranking RPF officials. After the release of the report, the UN Security Council was forced to admit the information had been in the ICTR’s possession the entire time at Arusha.

In hindsight, Hourigan and Bruguiere turned the entire history of the Rwandan Genocide on its head by effectively pointing to the RPF’s complicity in President Habyarimana’s assassination. Their reports paved the way for a revisionist trend in the historical scholarship of the genocide by providing a new generation of historians with the necessary evidence to critically reexamine Kagame’s misleading vision of the Hutu extremist. They also provided the ICTR with the requisite legal documentation to show that the Hutu extremist factions mentioned in the previous chapter, the Interahamwe and the Akazu, were not responsible for the shooting down of the Falcon 50.

The Interahamwe was founded by a Tutsi member of the MRND, Anastase Gasana, in response to the rise of the Inkuba, a youth group of the MDR that had fought against the MRND from July 10 1992 to July 13 1992.11 Bernard Lugan explains that Gasana left the MRND to join the MDR, where he became councilor for the Hutu Prime Minister Nsengiyaremye. By the end of the genocide, in July 1994, he had joined the RPF and was minister for Kagame’s first government.12 In hindsight, the “absence of MRND structural relationships and control over the Interahamwe” may have caused Gasana to change alliances amidst a congenial business environment between Hutu and Tutsi businessmen “who used mass killing to settle political scores.”13 In this context, Tutsis may conceivably have formed an important part of the Interahamwe.14

Being unknown, the Akazu faction was also misrepresented and slandered. Gaspard Musabyimana was a witness before the ICTR in the trials of Protais Zigiranyirazo, supposedly the head of the Akazu guilty of conspiracy to commit genocide, complicity in genocide and murder as a crime against humanity.15 The former testified on the basis of his experience as a civil servant in Rwanda that there was no known intervention by alleged inner-Akazu members between 1992 and 1994.16 Moreover, he argued in his book that those who claim to have knowledge on the Akazu are unable to define its structural and organizational properties.17 In hindsight, Musabyimana was correct. The ICTR was unable find evidence on which it could charge Zigiranyirazo for his crimes; it found that “the prosecution failed to prove that Protais Zigiranyirazo conspired with officials, at various meetings, to plan or facilitate attacks on the Tutsi population. Likewise, the Prosecution failed to prove any criminal responsibility for alleged involvement in the Interahamwe, or in killings on Rurunga Hill.”18 19

|

| Marc Trevidic and Nathalie Poux |

The relatively long chronology of the Hourigan, Bruguiere, and Trevidic reports – from 1997 to the present – shows that our international public legal system constantly suppresses people who, in their quest for greater historical accuracy, inadvertently threaten the official narrative. After the 1997 Hourigan report, for instance, the UN mysteriously suppressed all future ICTR investigations into the April 6 assassination, which bought Kagame precious time to uphold victors justice and consolidate his rule via a biased narrative. Today, however, the tide may be turning against Kagame, for Trevidic’s refusal to dismiss the April 6 1994 assassination is testimony to the tremendous evolution of knowledge on the genocide. The ICTR must take this new information into serious consideration if it is to guarantee all of the accused Hutus with a free, fair, and independent trail. Hopefully, with enough popular pressure from dissidents in the international community, the UN will no longer be able use the ICTR and the official narrative to cover up evidence for Kagame’s poor record in the African Great Lakes.

2. THE ROLE OF FOREIGN MILITARY AND ECONOMIC AID IN THE RPF’S RISE TO POWER

Having covered the unsound Hutu extremist narrative, now we can look into how the international community facilitated Kagame’s rise to power by adhering to the official Hutu extremist narrative. In the end, was it in the UN Security Council’s interest to facilitate Kagame’s bid to power through military and economic aid before and after the April 6 attacks? If so, did some forces threaten to counter the Hutu extremist narrative? To answer this set of questions, we will analyze the role of foreign military and economic aid given to Kagame during his rise to power. This methodology will in turn allow us to consider in the final chapter why the UN must reinforce victor’s justice to justify the chaos it created in the region, why it ascribes to a narrative that deliberately conceals the inapplicability of the Western common law and multiparty electoral systems in heterogeneous ethnic settings, and why it tasked the ICTR with suppressing all future evidence pointing to the RPF’s complicity in Habyarimana’s assassination.

Kagame: Freedom Fighter or Terrorist?

There is evidence pointing to the role of some UN Security Council members in providing military aid to Kagame while he lived in Uganda throughout the 1980s and well into the 1990s. The evidence exposes the international community’s curious tendency to sponsor corrupt political regimes, leaving the UN Security Council with little choice but to conceal its fraudulent behavior by deliberately ascribing to a narrative that falsely portrays Kagame as a freedom fighter.

It has become commonplace for the international community to watch on complaisantly as America and its allies cover up their blunders by positioning RPF terrorists at the heart of their wider strategy in the African Great Lakes region. Herman and Peterson argue that Museveni and Kagame have been able to ignore the ICC’s indictments because they are highly valued clients of the West.23 Even before the ICC was created, were it not for US military and economic support in the region, the international community would have sanctioned the RPF-led Ugandan invasion of Rwanda on October 1 1990 as a clear case of aggression, rather than as a mere side-effect of ongoing civil incursion or rising ethnic tensions.24 Everywhere in the world, Philpot adds, “that attack…would be described as an invasion of one country by another…In legal terms and according to principles established at the Nuremberg Trials…it was no less than the worst war crime because it was a crime against peace.”25 But Kagame got away with this war crime because the Anglo-American system of imperial domination used the Hutu extremist myth to successfully portray him as the leader of a group of freedom fighters rather than terrorists, thereby consolidating his position as “the global elite’s favorite strongman.”26

|

| President Yoweri Museveni |

Kagame invaded Rwanda shortly after becoming head of the RPF in 1990. Membership into the political party was accorded to “Uganda’s former Defense Minister, Fred Rwigyema, along with many senior officers, one hundred and fifty middle level officers, and even some of President Museveni’s own bodyguards.”30 Before the invasion, Museveni emphasized the importance of military rigor (discipline, loyalty etc.) in combating counterrevolutionary insurgencies. Yet, after the invasion, he conveniently distanced himself from the RPF by “pleading ignorance and surprise”, going as far as arguing in a 1991 address that its members “conspired, took us by surprise, and went to Rwanda, which was not particularly difficult…We had information…but we shared it with the Rwandan government. [The Rwandan government] actually had, or should have had, more information because, after all, it was their business…to follow up who was plotting what.”31 The Rwandan government, according to Museveni’s logic, was at fault for not having spied and monitored all the movements and actions of the Ugandan army.32 Museveni’s reluctance to view spying as a call for war is problematic not because it normally would not apply to neighboring countries like France and Germany (as Philpot has us believe), but rather because this logic is applicable only when it benefits the Anglo-American system of imperial domination. The Anglo-American empire allowed this type of thinking to safeguard Museveni against ever having “to punish the senior officers who mutinied in his own army” because it conveniently blamed Habyarimana for not containing the RPF’s attack.33 Shortly after the October invasion of Rwanda, the President of Uganda even demanded in a speech given to his officers in August 1990 “that Rwanda agree to a ceasefire and negotiate with the insurgents, now called the Rwandan Patriotic Front.”34

Why the myth of the Akazu genocide conspiracy lies at the heart of the official narrative of the Rwandan genocide – a reply to Keith Somerville.

Why the myth of the Akazu genocide conspiracy lies at the heart of the official narrative of the Rwandan genocide – a reply to Keith Somerville.

Here we should note that no imperial power ever once threatened to punish President Museveni or to cut off support to his country. In turn, Uganda was to maintain its role as the RPF’s military arsenal right up until the shooting down of the Falcon 50. Several months before the assassination, in February 1994, Jean-Pierre Minaberry, the copilot of Habyarimana’s presidential plane, expressed in a letter written in French to Bruno Decoin, the chief technician of the presidential plane, that:“With the RPF…located 1 km away from the control tower and given the UN alias MINUAR’s bias, we are almost certain that there are SAM 7 missiles and others posing a threat to the Falcon 50″.”35

Anyone who challenges the official narrative of Rwanda’s tragedy is inevitably accused of “˜denial’. This is the stock in trade of the Kagame regime’s treatment of its opponents, and on this Western upholders of his line are no better. Denial refers less to political analysis than to psychological disposition, and as such evades rational argument. More importantly, it has the odious implication of Holocaust denial and thereby often succeeds in closing down debate.

In hindsight, Bruguiere’s report justified the French pilot’s statement by pointing out that the missiles used to shoot down the Falcon 50 less than two months later came from a batch of 40 SA16 missiles sold to Uganda by the USSR in 1987.36 Moreover, the US ambassador to Rwanda at the time, Robert A. Flatten, who had close ties to Kagame and Museveni in the period leading up to genocide, testified before the ICTR that he “seriously doubted that Habyarimana’s supporters planned to kill civilians on a massive scale because the CIA and other intelligence agencies would have reported it when he was in Rwanda from 1990 to late 1993.”37

|

| Bill Clinton and Paul Kagame |

To completely remove Habyarimana from power, however, Kagame’s foreign allies also had to create strategic chaos in Rwanda through their economic aid.

Economic Aid

If Rwanda is at once small, crowded, and materially poor, then the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is large, empty, and materially rich. Hence, Kagame’s control of the DRC is crucial to his economic agenda. For twenty years now, the government of Rwanda has been pillaging the DRC of every resource, a practice that the Western world has not sanctioned. One reason for such corruption may be that the great trade-off of the Rwandan Genocide, the underlying reason why Kagame is portrayed as a ‘freedom fighter’, why the UN constantly suppresses evidence of the RPF’s involvement in Habyarimana’s assassination, and why his utterly ruthless rise to power is considered a success story, is that compliance with foreign economic interests is a requisite for avoiding US-imposed economic sanctions and military intervention.40 The government of Rwanda is no exception to this rule.

Proponents of the official narrative say the RPF invasion of Rwanda in 1990 triggered ethnic hatred against Tutsis and therefore probably increased the Hutu government’s legitimacy. This is true only insofar as we ignore the history of the conflict between Hutus and Tutsis. Habyarimana was considered a moderate Hutu and gained considerable support among both Hutus and Tutsis before Kagame’s attempts to overthrow him. A section of the French National Assembly’s Mission d’Information Parlementaire sur le Rwanda explains how Habyarimana helped redress Rwanda’s economic problems after rising to power in 1973:

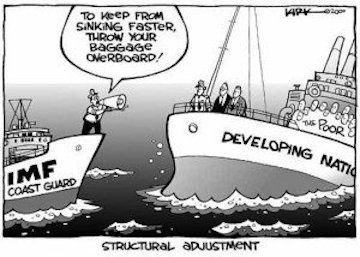

“During the 1970s, in fact, Rwanda was in good health financially and economically. This period was characterized by high economic growth rates (5 % on average), financial stability and a weak inflation rate. This situation resulted from high coffee prices and very prudent policy management. In this Rwanda, which was regarded as the “Switzerland of Africa”, the illusion of socioeconomic progress was strong between 1976 and 1983.” 41By 1980, NGOs flocked to Rwanda. Productivity growth reached its peak in 1986; some 42,000 tons of coffee were being exported from Rwanda, representing 82% of total exports.42 The development success of Rwanda was in large part due to Habyarimana’s ability to redress policies. In spite of his achievements, however, the situation started to deteriorate from the middle of the 1980s onward, when an agricultural crisis later morphed into a financial and political crisis, leading to increasing dependency on foreign aid (‘structural adjustment programs’) and a severe balance of payments deficit.43 The collapse of the mining sector, together with falling coffee prices, brought about a new crisis the Rwandan government could not control. The weakening of the state administrative apparatus severely affected almost all social groups by triggering the revival of ethnic hatred, made easier by the RPF invasion.44 Food production, which increased from 1960 to the mid 1980s, stagnated between 1985 and 1990.45 Moreover, Rwanda’s annual GDP growth rate fell from 4.7% in the 1970s to 2.2% in the 1980s, while its foreign debt increased from 189 million dollars to 873 million.46 47

To make matters worse, at the outset of hostilities in 1990, Rwanda became increasingly dependent on foreign aid. “The release of multilateral and bilateral loans since the outbreak of the civil war”, writes Chossudovsky, “was made conditional upon implementing a process of so-called ‘democratization’ under the tight surveillance of the donor community.”48 But poverty caused by civil war and IMF reforms precluded any genuine process of democratization. In fact, with the state administrative apparatus in disarray, state enterprises were pushed into bankruptcy and public services collapsed under the banner of “good governance.”49 The structural adjustment programs (SAPs) imposed on Rwanda by the IMF to restructure the Rwandan economy, such as the implementation of austerity measures on civilian expenditures, failed because donors had allowed defense spending to increase without impediment.50 Meanwhile, under a newly established social safety net and the growing threat posed by the AIDS epidemic, health and education collapsed and child malnutrition increased dramatically, which aggravated a demographic crisis that started in the 1960s.51

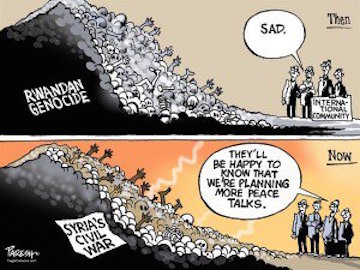

|

In spite of Habyarimana’s peace efforts, violence escalated to such an extent after his assassination that Rwanda went from being viewed as a potential success story in the early 1980s to an unsolvable ‘basket case’ in 1994. That year, the international community deemed the situation in Rwanda so unmanageable that it pushed “for the complete removal of UN troops because [it] didn’t want UN troops to stand in the way of Kagame’s conquest of the country, even though Rwandan Hutu authorities were urging the dispatch of more UN troops.”56 The UN, which had been inactive during the genocide, was afterwards forced to uphold victor’s justice to justify the socio-political and financial chaos it had created in the region. Therefore, it created the ICTR and tasked it with upholding the Hutu extremist narrative at all costs through the common law system. Later on, this assignment also required suppressing all future evidence pointing to the RPF’s complicity in Habyarimana’s assassination.

3. FROM THE ACCORDS, THE GENOCIDE AND THE ICTR, TO UNCONTESTED DIPLOMATIC IMMUNITY FOR KAGAME

Today, the UN Security Council is in a vulnerable position because it must conceal the fact that its championed multiparty electoral system, which was designed to replace Habyarimana, turned out advantageous to him. Hence, to preserve its legitimacy, the UN omitted from taking into account the evolution of knowledge on the genocide by tasking the ICTR with suppressing all evidence pointing to the RPF’s complicity in Habyarimana’s assassination. To suppress all evidence, it had to install a common law system that a) renders the prosecutor entirely independent before the ICTR and b) separates the plaintiff and defendant into two opposing albeit unequal camps. So long as the international community remains caught in this inefficient legal system, the history of the genocide cannot be rewritten, for the ICTR can carry on concealing Kagame’s crimes against humanity without meeting any real opposition.

The Arusha Accords and the Paradox of Majoritarian Multiparty Elections

The day after Habyarimana’s assassination, on April 7, 1994, the RPF violated the Arusha Accords by resuming hostilities unilaterally. In the end, why did the Arusha Peace Agreement, signed on August 4 1993 by the Hutu government and the RPF, fail to protect the people and reconcile the country? Why did Kagame violate the terms of the Arusha Peace Agreement? Part of the answer to both questions is that multiparty elections, which were meant to remove the ‘ethnic hating’ and ‘despotic’ Juvénal Habyarimana from power, ironically favored him. Aware of his disadvantage visavis Habyarimana, Kagame forwent the formal democratic process and engaged instead in armed conflict.

By 1990, Habyarimana had accepted that some reforms to Rwanda’s political process were needed, and in July, under pressure from Western aid donors, he announced his support for them. Although the RPF had broken ceasefire several times between 1990 and 1991, Habyarimana nevertheless agreed to install multipartyism and promulgated this constitutional change in June 1991.57 By August 1991, opposition parties were constitutionally recognized, and on April 2 1992, a coalition government that included all the major parties (MRND, MDR, PSD, PDC, and PL) was created. From then on, the four main opposition parties to Habyarimana’s MRND, Philpot tells us, “had to define their positions with regards to President Habyarimana, but they also had to define themselves in relation to the occupying RPF army and its supporters throughout the world.”58 Indeed, since the most important stakeholders – Belgium, the US, Canada, and Britain – backed the RPF and were prepared to eject President Habyarimana from power, opposition parties had to appeal to them in order to receive funding and other benefits.59 According to Philpot, most of these foreign powers appeared at the time to be siding with the invading RPF army:

“Seeing the way the wind was blowing, these opposition parties began to establish direct ties with the RPF in the hope of gaining similar international support for themselves. As a result, leaders of opposition parties and the Rwandan Patriotic Front met in Brussels from May 29 through June 3, 1992, and issued a joint press release. It turns out, in fact, that those meetings were attended by opposition parties.”60

Nearly 48 hours after the issuing of this joint press release, on June 5 1992, the RPF’s military wing, the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), launched a violent attack on the Byumba region and successfully fended off RAF forces, the Hutu government’s army. The invasion forced thousands of peasants into exile and somehow allowed the RPF to call the region a ‘liberated zone.’61 That same night, while the RPF was in Paris conducting political negotiations with the Rwandan government, French forces intervened in the region to support the RAF and mitigate the havoc wreaked by the RPA.62 In hindsight, had the French government not provided military support to the RAF, one can say Kagame would have used his growing political and military powers (in the RPF and RPA, respectively), along with Habyarimana’s absence from Rwanda, to achieve total victory long before the advent of genocide.63

Nearly 48 hours after the issuing of this joint press release, on June 5 1992, the RPF’s military wing, the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), launched a violent attack on the Byumba region and successfully fended off RAF forces, the Hutu government’s army. The invasion forced thousands of peasants into exile and somehow allowed the RPF to call the region a ‘liberated zone.’61 That same night, while the RPF was in Paris conducting political negotiations with the Rwandan government, French forces intervened in the region to support the RAF and mitigate the havoc wreaked by the RPA.62 In hindsight, had the French government not provided military support to the RAF, one can say Kagame would have used his growing political and military powers (in the RPF and RPA, respectively), along with Habyarimana’s absence from Rwanda, to achieve total victory long before the advent of genocide.63The point here is that, from the outset, the Arusha Accords largely favored the RPF. When a large transitional government was in turn established on August 3 1993, along with an international ad hoc tribunal the following year, their provisions logically favored the RPF. After the 1993 Peace Agreement, for instance, the new national army, which fused the Hutu RAF and Tutsi RPA, was to be composed of 19,000 men including 6,000 gendarmes, 60% of which came from the RAF and 40% from the RPA.64 Moreover, the chief of staff was to be an RAF member while the chief of the gendarmes was to be an RPA.65 Finally, since the commandant positions were to be distributed equally (50-50), 40% of RAF soldiers and up to half of its officers were removed from their positions, which instigated popular jealousy and hatred of Tutsis.66 To make matters worse, the transitional government, which was to comprise twenty ministers and secretaries of state, provided the MRNA and RPF each with five ministers.67

The incredible parity of these reforms is inexplicable given that the Tutsi population at the time comprised no more than 15% of the Rwandan population. Yet, rather than having the effect of triggering a movement for Hutu unity under the banner of ‘Hutu Power’ (as the official narrative has us believe), these reforms in reality divided the Hutu opposition by rallying some of its members towards the RPF’s familiar cause: namely, removing the Habyarimana from power. After all, the Rwandan Democratic Movement (RDM) and Liberal Movement (LM) parties imploded due to internal conflicts, which had the effect of replacing the tripolar balance of power anticipated at Arusha (Hutu opposition vs. Presidential Movement vs RPF) with a bipolar balance of power centered on Rwanda’s military-industrial complex (MRND/FAR vs. RPF/RPA).68

Despite this advantageous scenario for the RPF, more Hutus ended up joining the MRND. These Hutus were immediately labelled ‘extremists’ by the mainstream news media in the West; the ‘moderate’ label was reserved for Hutus who were allied to the RPF. Ultimately, the splitting of the Hutu opposition ascertained the fact that the RPF would lose the majoritarian elections at the hands of the MRND. In the typical irony of history, the majoritarian multiparty electoral system, which was introduced to remove Habyarimana from power, turned out to be mathematically advantageous (on ethnic grounds) for the sovereign himself. Put differently, Habyarimana would likely have won the elections with the Hutu majority vote had Kagame not logically decided to let go of the democratic process in favor of manipulation, armed conflict, assassination and eventually genocide.

The official narrative does not take these ethnic realities into account because they highlight the inapplicability of Western ‘democracy’ in Rwanda. To make up for its ignorance, the UN Security Council had to preserve the legitimacy of its official narrative. After the genocide, it did this by exploiting a number of loopholes in the Anglo-Saxon common law system that prevented the ICTR from taking into account the evolution of knowledge on the genocide.

The ICTR and the Common Law System: Manipulating numbers to Uphold the Narrative and Consolidate Victor’s Justice

To this day, a disproportionate number of the prosecutions have been brought against the Hutus, part of the reason for which is that Kagame’s government refuses to provide information that could be used to prosecute alleged Tutsi perpetrators.69 70 For example, Ramsey Clark’s 2004 letter to Kofi Annan, the head of the UN’s Peacekeeping Operations at the time, expressed concern that the ICTR had failed to indict a single Tutsi after nine years, even though Faustin Twagirimungu, the RPF’s first minister in 1994 and 1995, had testified that more Hutus than Tutsis were killed during the Rwandan genocide.71 Furthermore, the lieutenant Abdul Ruzibiza, a former officer for the RPA and Kagame’s comrade in arms, added in his testimony that the RPF counted Hutu corpses as Tutsi corpses: “I am convinced that the exhumed bodies of the common graves are not only those of Tutsi, because I know common graves where the Inkotanyi [Tutsi combatants] randomly threw the bodies of the people they killed, they were exhumed together by qualifying them all of Tutsi.”72 This observation is plausible, for there were not enough Tutsis in Rwanda to explain the number of victims put forward by the RPF after the genocide. In fact, by 1991, there were only 596,387 Tutsis out of a total population of 7,099,844 (or 8.4%). After the genocide, however, the RPF estimated that the total number of victims amounted to 1,074,017, and 93.7% of them were Tutsi (therefore 1,006,353 Tutsis in total, or almost twice the Tutsi population of Rwanda).73

|

| Christian Davenport and Allan C. Stam |

The ICTR as an Ideologically Incoherent Instrument of Foreign Political Power

During the genocide, the Security Council did not intervene in the conflict, despite having the power and responsibility to do so. After the genocide, it stepped outside of its powers to establish a tribunal: in November 1994, Security Council Resolution 955 created the ICTR “for the prosecution of persons responsible for genocide and the other [...] violations of international humanitarian law [and] ensuring that such violations are halted and effectively redressed.”75 76 By then, Kagame had won the war, established military control over the entire Rwandan territory, and justified his victory by calling upon a narrative that appealed to the Security Council. In this context, all there was left to do was to reinforce victor’s justice by judging the losers.77

Since the Security Council created the tribunal under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations to set out the UN Security Council’s powers to maintain peace, judging the losers would emanate from the Security Council itself rather than, as it should, “from the General Assembly of the UN representing all states on an equal footing.”78 Therefore, from the outset, “the tribunal was created as an instrument to carry out the Security Council’s policing or coercion functions.”79

Philpot believes these functions should be independent from justice, but this is wishful thinking, for the ICTR cannot possibly be independent under an anglo-saxon common law system that a) renders the prosecutor totally independent before the ICTR and b) creates a deadlock plaintiff-defendant opposition.

Targeting the Prosecutor

Under the common law system, the prosecutor is not subject to the tribunal’s authority, but rather that of the UN, and more specifically, the permanent members of the Security Council.80 Since the US and Great Britain, for instance, have always opposed any investigation that could potentially bother the RPF, the court never pursued Kagame or his collaborators once the RPF became a murder suspect. This argument explains why the court declared the investigation to be outside of its mandate. 81 It also explains why the Court of First Instance of the ICTR still refuses to take into account testimonies that incriminate Kagame on the grounds that they are not “essential to truth seeking”, a decision that the Court of Appeal is not shy to uphold.82

Philpot rightly argues that the compliance of many ICTR prosecutors towards the US and its foreign policy is an indicator that they similarly knew to whom they were indebted. The driving factor behind this consensus is the heavily occidental training all prosecutors forcibly underwent to compensate for the total disorder in Rwanda’s Justice Ministry.83 84 William Schabas, for instance, headed the program for training and recruiting Rwandan jurists as a Canadian member of the International Commission of Inquiry Concerning Rwanda.85 According to Carrol Off, the Eurocentric questions that the candidates had to answer included multiple-choice questions on Plato’s Republic, Jean-Paul Sartre, and the capital of Canada.87 She goes on to write:

“Anyone who could pass the one-hour test qualified for a fast track training program that lasted anywhere from one to five months. At the end of it, successful candidates were declared to be qualified prosecutors, investigators, and judges. Formal education had never really been an issue in Rwanda, where only one in fifty judges of the pre-war judiciary had a degree in law.”86If prosecutors had to be heavily influenced by Western dogma to earn a position at the ICTR, then chief prosecutors were no different. Richard Goldstone, for example, had ties to the CIA.88 Moreover, we established earlier on that Louise Arbour had ordered Hourigan to come to The Hague in 1997, where she mysteriously told him to drop the investigation and “to burn his notes” without providing much of an explanation for her change of mind.89 Finally, Carla Del Ponte curiously contradicted herself in December 1999 when she declared that all events contributing to the genocide’s “preparation” were within the ICTR’s mandate except for the one assassination she holds responsible for having “triggered everything”:

“If the tribunal does not handle (Habyarimana’s assassination), it is because it does not have jurisdiction in the matter. It is very true that it triggered everything. But in and of itself, attacking the plane and killing the president are not acts that falls under the articles that give us jurisdiction.”90The Battle Between Two Opposing Camps: Plaintiff vs. Defendant

We have yet to find a way to incriminate Kagame for his crimes because formal international public law is a necessary but slow process. It is a slow process because the common law system ultimately creates two opposing camps, the plaintiff and the defendant, in order to subject the ICTR to an official narrative that inaccurately assigns Tutsi criminals the role of plaintiff and Hutu criminals the role of defendant.91

|

The point here is that ICTR prosecutors are subservient to the political, economic, and military interests of the Anglo-American oligarchy, which creates a situation where politics trumps international justice and bias trumps inquisitiveness, thereby allowing Kagame and his Western allies to cover up their poor record in the African Great Lakes Region.

4. CONCLUSION

Given its reluctance to investigate the RPF’s complicity in the Habyarimana assassination, the ICTR may or may not be able to deliver its promise of providing many of the accused Hutus with their most fundamental right to a free, fair, impartial and independent trial. What is clear, however, is that ICTR is inadvertently putting the UN Security Council in the hot seat by carrying evidence that a) undermines the fraudulent official account of the genocide, b) exposes the role of some UN Security Council members in facilitating the RPF’s rise to power, and c) points to the inapplicability of the UN’s championed common law and multiparty electoral systems in heterogeneous ethnic settings. As a result, the UN Security Council is left with little choice but to preserve its legitimacy by coercing the rest of the international community into ignoring the evolution of knowledge on the genocide.

This triple threat explains why hardly anyone speaks of the US-Rwanda connection in not having signed the 1998 Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court. It also explains why Kagame can claim diplomatic immunity and continue to exercise his hegemonic influence in the Great Lakes region without signing the Rome Statute. Therefore, until diverse nations unite in common cause to revise (rather than sustain) the Hutu extremist narrative, politics most likely will continue to trump justice, bias will trump inquisitiveness, and international public law will remain an inherently slow, informal, and unfair process.

On a more positive note, the rising popularity of alternative news indicates that more dissidents realize they are being lied to by the mainstream media. They know the mainstream press cannot cover up much longer the fact that Western democratic values make no sense in heterogeneous ethnic settings like Rwanda, where the common law system and majoritarian multiparty elections exacerbate ethnic tensions.

The main threat to dissidents around the world remain those progressive and neo-conservative intellectuals who, because they do not grasp the ethnic realities of the African continent, carry on promoting an over-simplified official narrative (via the mainstream press) that justifies the Anglo-American system of imperial domination. Equally threatening are left-wing and right-wing political parties, most of which are subservient to this intellectual elite, that mobilize in the name of human rights, pacifism and universal fraternity while covertly sponsoring corrupt and bellicose heads of state.

Again, people are starting to notice this political trend, which is probably why the US recently warned Kagame not to seek a third term as Rwandan president. What remains to be seen, however, is whether or not the US and the rest of the international community will incriminate Kagame once he no longer has sovereign immunity. This pending decision puts the world at a dangerous crossroads: if the international community does decide to bring Kagame and his men to justice, it will have to go against its own interests either by debunking the Hutu extremist myth and re-writing the official history of the Rwandan Genocide, or alternatively by fabricating yet another lie and further promoting the intellectual enslavement of mankind.

The Truth can be buried and stomped into the ground where none can see, yet eventually it will, like a seed, break through the surface once again far more potent than ever, and Nothing can stop it. Truth can be suppressed for a "time", yet It cannot be destroyed. ==> Wolverine

Subscribe to:

Post Comments

(Atom)

The 1994 Rwandan genocide is known worldwide

Rights of Victims Seeking Justice

Survivors Speak Out: Advocating for Justice and Compensation for Victims of the RPF Genocide We are thrilled to announce an exciting new collaborative project, spearheaded by Jean-Christophe Nizeyimana, the esteemed economist and human rights activist, as the founder of AS International. This initiative aims to amplify the voices of survivors and shed light on the ongoing quest for justice and reparations. Join us to uncover critical insights about the mastermind behind the Rwandan Genocide who remains at large, evading accountability. Stay informed and take part in this vital movement for justice and human rights.

Profile

I am Jean-Christophe Nizeyimana, an Economist, Content Manager, and EDI Expert, driven by a passion for human rights activism. With a deep commitment to advancing human rights in Africa, particularly in the Great Lakes region, I established this blog following firsthand experiences with human rights violations in Rwanda and in the DRC (formerly Zaïre) as well. My journey began with collaborations with Amnesty International in Utrecht, the Netherlands, and with human rights organizations including Human Rights Watch and a conference in Helsinki, Finland, where I was a panelist with other activists from various countries.

My mission is to uncover the untold truth about the ongoing genocide in Rwanda and the DRC. As a dedicated voice for the voiceless, I strive to raise awareness about the tragic consequences of these events and work tirelessly to bring an end to the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF)'s impunity.

This blog is a platform for Truth and Justice, not a space for hate. I am vigilant against hate speech or ignorant comments, moderating all discussions to ensure a respectful and informed dialogue at African Survivors International Blog.

Human and Civil Rights

Human Rights, Mutual Respect and Dignity

For all Rwandans :

Hutus - Tutsis - Twas

Rwanda: A mapping of crimes

Rwanda: A mapping of crimes in the book "In Praise of Blood, the crimes of the RPF by Judi Rever

Be the last to know: This video talks about unspeakable Kagame's crimes committed against Hutu, before, during and after the genocide against Tutsi in Rwanda.

The mastermind of both genocide is still at large: Paul Kagame

KIBEHO: Rwandan Auschwitz

Kibeho Concetration Camp.

Mass murderers C. Sankara

Stephen Sackur’s Hard Talk.

Prof. Allan C. Stam

The Unstoppable Truth

Prof. Christian Davenport

The Unstoppable Truth

Prof. Christian Davenport Michigan University & Faculty Associate at the Center for Political Studies

The killing Fields - Part 1

The Unstoppable Truth

The killing Fields - Part II

The Unstoppable Truth

Daily bread for Rwandans

The Unstoppable Truth

The killing Fields - Part III

The Unstoppable Truth

Time has come: Regime change

Drame rwandais- justice impartiale

Carla Del Ponte, Ancien Procureur au TPIR:"Le drame rwandais mérite une justice impartiale" - et réponse de Gerald Gahima

Sheltering 2,5 million refugees

Credible reports camps sheltering 2,500 million refugees in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo have been destroyed.

The UN refugee agency says it has credible reports camps sheltering 2,5 milion refugees in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo have been destroyed.

Latest videos

Peter Erlinder comments on the BBC documentary "Rwanda's Untold Story

Madam Victoire Ingabire,THE RWANDAN AUNG SAN SUU KYI

Rwanda's Untold Story

Rwanda, un génocide en questions

Bernard Lugan présente "Rwanda, un génocide en... par BernardLugan Bernard Lugan présente "Rwanda, un génocide en questions"

Nombre de Visiteurs

Pages

- Donate - Support us

- 1994 MASSACRES IN RWANDA WERE NOT GENOCIDE ACCOR...

- Les massacres du Rwanda 20 plus tard. À la recherc...

- About African survivors International

- Congo Genocide

- Twenty Years Ago, The US was Behind the Genocide: Rwanda, Installing a US Proxy State in Central Africa

- Rwanda Genocide

- Our work

Popular Posts - Last 7 days

-

[ Since 1994, the world witnesses the horrifying Tutsi minority (14%) ethnic domination, the Tutsi minority ethnic rule with an iron hand,...

-

April 16th, 2009 Mr. Abramowitz: What a shame! How could you support the heavyweight criminal the world has ever hosted? How could you dare...

-

Sweden stops aid to Rwanda after UN report Sweden is suspending all aid for the government of Rwanda. Sweden’s Aid Minister Gunilla C...

-

Fifteen years ago, efforts at genocide killed about 800,000 Rwandans . Now that tragedy is providing the government with a cover for repre...

-

10.08.2009 Deux bailleurs de fonds, en l’occurrence la Suède et les Pays Bas, maintiennent la suspension de leur aide budgétaire directe au...

-

Rwanda Tribunal Should Pursue Justice for RPF Crimes Failure to Act Risks Undermining Court’s Legacy December 12, 2008 on biased empty j...

-

dinsdag 7 april 2009 10:44 Nederland moet de steun aan Rwanda volledig stopzetten. Dat eist VVD-Tweede Kamerlid Arend Jan Boekestijn. '...

-

Ponerogenic processes take place in Rwanda since 1990. People continue to be assassinated. Relatives are in a state of being unuble to repo...

-

Ladies and Gents: If we truly want peace in this world, we need to make better choices closer to home. I recently have heard that many of we...

-

Éénvandaag 10 Avril 2009 *** Aujourd'hui, 15 ans après le génocide au Rwanda, la situation pourrait changer de mieux en mieux dans ce p...

Archives -future generations to learn from the past

Everything happens for a reason

Bad things are going to happen in your life, people will hurt you, disrespect you, play with your feelings.. But you shouldn't use that as an excuse to fail to go on and to hurt the whole world. You will end up hurting yourself and wasting your precious time. Don't always think of revenging, just let things go and move on with your life. Remember everything happens for a reason and when one door closes, the other opens for you with new blessings and love.

Hutus didn't plan Tutsi Genocide

Kagame, the mastermind of Rwandan Genocide (Hutu & tutsi)

0 comments:

Post a Comment